For reasons uncertain (I was a somewhat boring youth who didn't hang around at loud concerts for instance) I have fairly strong tinnitus, which can be a nuisance. Different people report different manifestations, but mine sounds like a chorus of insects - tree crickets or higher-pitched cicadas in particular. This means that I can't always tell if the chorus I'm hearing emanates from inside or outside my head but a week or so ago, during a family visit to Nowra in near-coastal southern New South Wales, I was in no doubt whatsoever.

Like many cicada species, the very handsome Redeye Psaltoda moerens doesn't appear every year in any given locale, but this year appears to be theirs in that part of the world. From quite early in the day, as the temperature rose towards 20 degrees, the roar of the massed Redeyes filled the world. After a while the steady roar breaks into what's known in the cicada students' world, somewhat quaintly, as 'yodelling'; it sounds like a sawing but melodious "cheee-aw-chee-aw-chee-aw (etc!)"

The aggregations typical of this species - and others - can be enormous; I watched a constant stream of Redeyes flying from tree to tree in the yard. They gather to mate, with the males striving to capture the females' attention by the force and persistence of their song.

| A few of the Redeye gathering on just one tree - and many had flown away as I approached. |

| A successful suitor. |

This gathering had its genesis in a past one, though for most Australian cicadas we don't know the length of the cycle, though it seems to be some years at least for many species. Like her mother before her, this female will lay her eggs in dead eucalypt branches; they will hatch in 10 to 12 weeks, when the tiny nymphs will hurry down to the ground and enter soil cracks, where they will insert their proboscis into a tree root. The liquid waste they exude helps form a wall to their cell. This is how a cicada spends most of its life - the adult phase that either thrills or exasperates us, depending on our approach to nature, lasts probably no more than four weeks at the most. When the time is right, some years later, the nymph comes up to the light, climbs onto a convenient surface and emerges from the shell at night.

| Redeye nymph cases; on the left-hand one the split can be seen along the back where the adult emerged. |

Much of the male Redeye's body is designed to sing - his abdomen forms a fearsome resonating chamber, as we can attest, amplifying the sound made by vibrating timbals, corrugated membranes like a wobbleboard on his sides just in front of the abdomen. His song is unique to his species. The energy required to drive it at up to 100 vibrations a second is significant, which is why he can only sing when the temperature reaches a certain level.

He is a bug - no, really, a member of the Order Hemiptera, characterised by a long sucking proboscis.

|

| Sap-sucking Hemipteran, Kata Tjuta, central Australia. Cicadas all have such a proboscis (more properly a rostrum), both as nymphs and adults, though it it generally kept tucked away under the body. |

The adults insert the rostrum gradually into the bark, inserting saliva and extracting partly digested sap. This is dilute food, and a considerable quantity of water is constantly sprayed from the trees where large numbers of cicadas are feeding. Feeding need not be interrupted by either singing or mating incidentally!

More than one cicada species can cohabit, though only one was present this time, as far as I could see. In a recent Nowra summer however the gorgeous Yellow Mondays were abundant.

|

| Masked Devil, still the same species as the Yellow Monday. |

Other colour forms of this species are known as Chocolate Soldier, Greengrocer and Blue Moon.

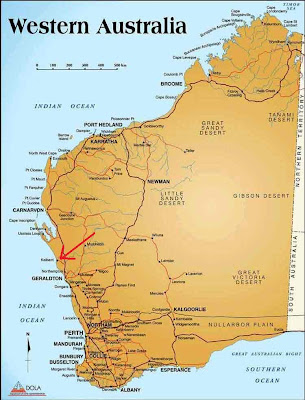

Closer to home, around Canberra, cicadas are not as prominent as nearer the coast, though some years we too have massive Redeye eruptions, when a variety of bird species live well for a few weeks. Even up in the Snow Gums in the mountains however cicadas can be found, though the great choruses are rarely heard.

As for overseas cicadas, I'm afraid I can't even offer a guess at the identity of this Andean specimen; again, help welcomed!

| Cicada, Cuenca, 2500 metres above sea level, Ecuador. |

Cicadas are one reason I look forward to summer (or maybe I like cicadas so much because they are emblematic of summer for me). But, you know one good thing about tinnitus? I can hear cicadas all year round!

BACK ON MONDAY

+Kalbarri+0808.jpg)

+Chichester+SF+1207.jpg)

+Nowra+1006.jpg)