I'm a big fan of woodlands; OK, I like any natural habitat, but the openness of woodlands, along with their generally rich wildlife, makes for a great natural history experience. Generally you go to central-west Africa primarily for rainforest, but there are some great woodland reserves too, and Bénoué National Park in central Cameroon is a treasure. It's huge - some 180,000 hectares - and has been reserved for over 80 years; it was officially declared a national park in 1968.

|

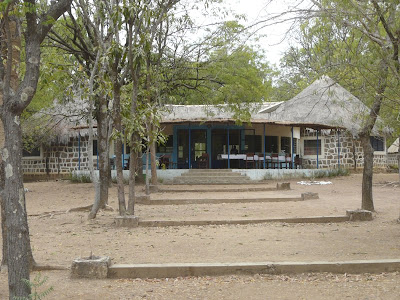

Woodland, Benoue National Park |

|

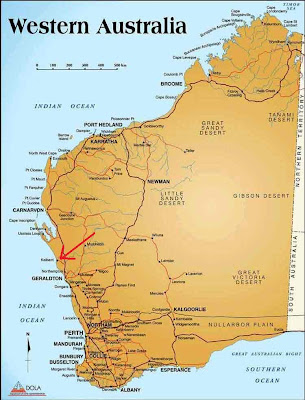

| Benoue National Park is indicated by the red arrow, bounded to the east by the Benoue River and to the west by the main south-north highway. |

Cameroon is not always an easy country for westerners; infrastructure is widely dilapidated, roads are often appalling, and the regular military and police road blocks (whose main purpose is to extract petty bribes from drivers) can be intimidating. Nonetheless, there is not evident grinding poverty and people in general are cheerful and welcoming. Given the levels of corruption reported, I was not optimistic about the state of the parks - indeed we were warned that poaching had seriously damaged Bénoué - but in the event this park at least had good levels of fairly relaxed wildlife. It is surrounded by hunting 'reserves'.

|

| Loder's Kob male, Kobus loderi, Benoue National Park. This relatively recently recognised species is found across central Africa from Nigeria to western Sudan. |

Accommodation in the park is basic but quite adequate, a mix of traditional rondavels (yes, I realise that's a South African term, but it's what they look like!) and less elegant rooms, set above the mostly sandy river.

|

| Benoue accommodation. ('My' room below.) |

|

| Dining room - however it's a case of 'bring your own cook'! |

An aspect perhaps unexpected to an Australian at least was the presence of people living in the park. I know nothing of their history; it could be that their families were there when the park was declared. One assumes there must be some impact on wildlife, but again I'm unable to comment.

|

| Children of Benoue; I couldn't make out what the game was. |

Nonetheless, there were certainly mammals to be seen immediately below the accommodation, in the river bed.

|

| Olive Baboon Papio anubis; not tame, but not intimidated by us. A powerful species, found right across central Africa. |

|

| Red-flanked Duiker Cephalophus rufilatus; tiny and shy! |

We spent a lot of time by the river, but en route we did see some impressive birds.

|

| Abyssinian Ground Hornbills Bucorvus abyssinicus; very early morning, not much light - sorry. In the case of their facial adornments, it's blue for girls, red for boys. |

|

| Black-bellied Bustard Lissotis melanogaster female. Unlike some of the species already mentioned, this superb beast is found throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa. |

|

| This however was our destination and we spent a very pleasant and rewarding morning here - though the residents (below) were highly suspicious of us. |

The main goal was the rare and localised Adamawa Turtle-Dove Streptopelia hypopyrrha, a west African special - we didn't see it there, but to be honest I was more than happy with what I did see, though the light was awful, overcast and glarey, as you'll see in the following pictures.

I also saw a bird I never thought to - the strange Egyptian Plover Pluvianus aegyptius, not a plover, long thought to be a pratincole, now given its own family Pluvianidae all to itself.

|

| Egyptian Plover, also called the Crocodile Bird for its supposed habit of providing dental hygiene service to crocs; sadly this doesn't actually seem to be based on fact. |

Two kingfishers - none the less delightful for being common species and widespread through Africa - featured at the waterhole too. Unlike most kingfishers, these two actually do make a living plunging for fish and other water animals.

|

| Giant Kingfisher Megaceryle maxima; this beauty lays claim to being the world's largest kingfisher, though the title is hotly disputed by our own Laughing Kookaburra. |

|

| Malachite Kingfisher Alcedo cristata, is one of the smallest, barely a quarter the Giant's size. |

The bee-eaters, one of my favourite bird groups, are kingfisher relatives (same Order anyway), and this was the first time I'd seen the glorious Red-throated Bee-eater Merops bullocki.

|

| Red-throated Bee-eater, being especially confiding. |

It was hot, the beer at the accommodation was room temperature (ie about 35 degrees), the water pump wasn't working (so no showers or flushing toilets) and the little sweat bees were relentless.

Nonetheless I remember Bénoué fondly. Oh, and in the end we did see the Adamawa Turtledove, albeit somewhat distantly!

I don't suggest you alter your travel plans to take in Bénoué - or even Cameroon, though there's plenty to see there - but if you happen to be in the area...

BACK ON THURSDAY

+SRNP.jpg)

+Kalbarri.jpg)

+Bigga+Cemetery+1007+vert.jpg)

+TdPNP+1107.jpg)

+Kalbarri+0808.jpg)

+Gregory+NP.jpg)

+Kalbarri+0808.jpg)

+Badgingarra+NR+0808.jpg)