It mattered to me when I was a boy, getting taken to Tarzan movies for the animals. (I was less keen on the mandatory quicksand scenes and Loyal Native Bearers falling off narrow cliff tracks.) But I would be inevitably infuriated by what were to me monumental gaffes, such as having the wrong elephants in Africa!! (On the other hand I was quite relaxed about the preposterous basic premise of the story, which says something about me.)

![]() |

I can't say for certain if this is Johnny Weissmuller (the US Olympic swimmer turned

archetypal Tarzan) but I can say with authority that these are Indian Elephants! |

My search for screen animals broadened when the family up the road got a telly in the 1950s (or maybe early 1960s), and I used to go up to watch Jungle Jim in black and white. My boyish fury was unabated. Unlike Tarzan it wasn't always clear where it was intended to be set, but it didn't matter much - the combination of animals was wrong!

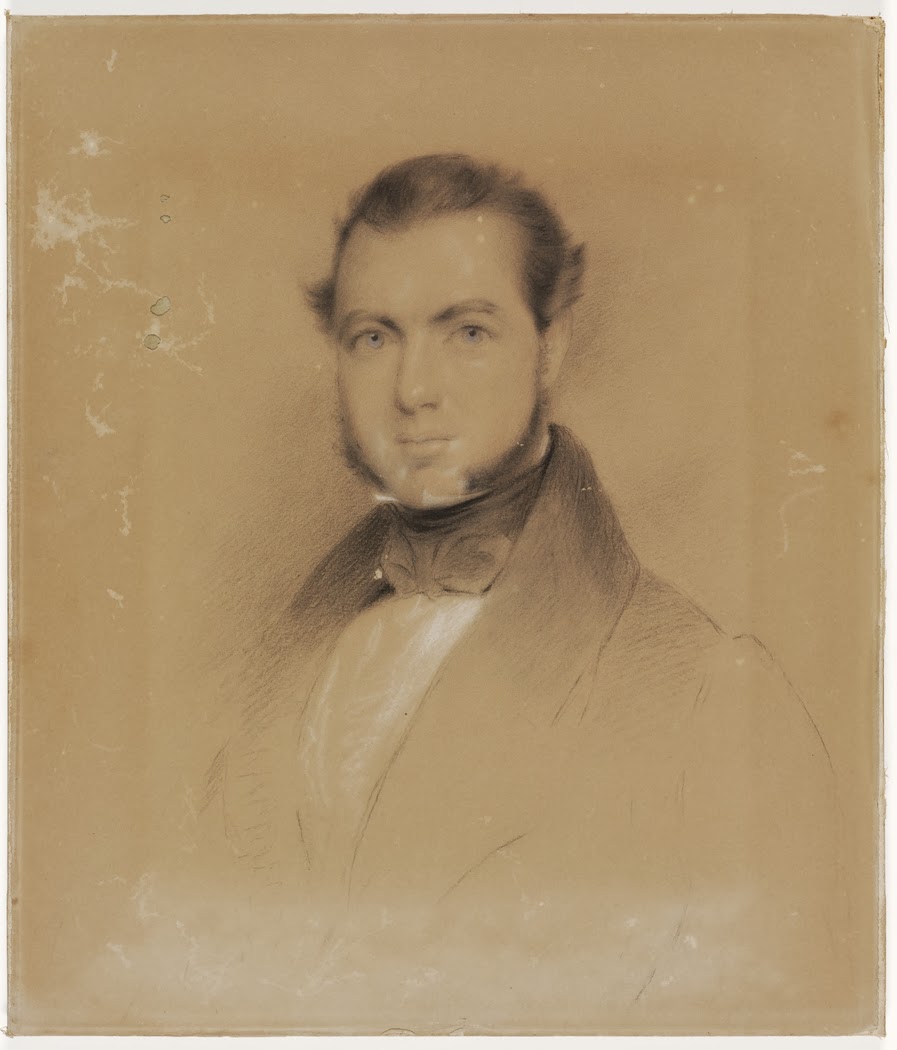

![]() |

Grant Withers, the original Jungle Jim.

The would-be man-eating lion seems to be asleep (or worse) but that wasn't my main concern. |

![]() |

Withers was in time supplanted by Johnny Weissmuller, looking for a life after Tarzan.

And the tiger supplanted the lion (though I recall it was pretty random). I gather the original comic book series

was based in South-East Asia (in which case a tick for the tiger) but it was not at all clear

where the TV series was supposed to be. |

And of course every 'jungle' movie ever made, including Tarzan and the Jungle Jim series, whether set in Africa, Asia or South America, includes as an essential element of the sound track Australian Laughing Kookaburras, South American Screaming Pihas, and Asian Green Peafowl (peacocks).

![]() |

Both the Screaming Piha Lipaugus vociferans, Sacha Lodge, Ecuador, above

and the Laughing Kookaburra Dacelo novaeguineae, Canberra, below,

would probably be most surprised to hear their own impressive and distinctive voices ringing

out above Tarzan's head, Wherever-he-is in Africa. |

My interest in this aspect of entertainment was unexpectedly reawakened over the weekend, when we went to see the movie Tracks, based closely on the 1978 book by Robyn Davidson of her truly remarkable solo camel trek of some 2000km west from Alice Springs to the Indian Ocean. (To be honest I don't go to many movies, so I'm not about to set up as film critic, but I enjoyed this one, especially the landscapes, while not entirely seeing what it added to the book.)

But.... In a scene not from the book, whose significance evaded me entirely, a large python slips across the sleeping 'Davidson' deep in the western deserts.

![]() |

Irrespective of the purpose of the scene (I'm sure it will be immediately obvious to you), there's a

very fundamental problem. Carpet Pythons Morelia spilota, which this undoubtedly is, do not occur

anywhere near the western deserts - indeed there are no large pythons at all in the vast sandy tracts.

You can see the scene briefly here, at the 1 minute 27 second mark; being technologically limited, and

unable to find a still of the scene, I photographed it from this promo on my computer screen, hence the poor quality! |

(There was another little blip to upset the biologist too, albeit not biogeographical; a Euro is shot for food by an Aboriginal elder, but mysteriously turns into a female Red Kangaroo when dead! The Euro only appeared briefly, and I'd like to see it again, but I tend to trust myself on this. On the other hand if it was a make of car, say, they could get away with anything as far as I'm concerned!)

Another famous bioblunder I recall from way back - though at least I was at uni by then - was the inexplicable insertion of Brazilian Tapirs Tapirus terrestris into a scene at the start of the epic 2001: a space odyssey. The problem is that the scene was set in the early days of human evolution - quite rightly in Africa.

![]() |

The black hairy ones are our ancestors - the tapirs (whose alternative name South American Tapir says

it all really) are... well who knows?! |

I hardly expect cartoons to be scientifically rigorous, but still... I recall Antz, an animated movie (yes, about ants - I can't explain the 'z') from the late 1990s. All the soldiers were explicitly male!

![]() |

As most of us could have told them, ALL useful members of an ant colony, most certainly including

the soldiers, are exclusively female. |

One I didn't see was Lion King, but I have read about the opening scenes, featuring

leafcutter ants above the savannah.

![]() |

| Oops, sorry - only in South America! |

Another I didn't see was Jurassic Park, but acting on a tip-off I looked up the amber-trapped mosquito which carried the dinosaur DNA (and I'm not getting into that one here!).

![]() |

Very nice, but the lovely plumed antennae tell us that it's a male -

and only female mozzies feed on blood. Males are staunch vegetarians. |

Another I managed to miss was the apparently history-annihilating 300, featuring Persians versus Spartans. The Persians apparently brought 'war rhinos' to the party - interesting concept, though I'd be fascinated by the logistics of training and control. However the movie makers fell into the Tarzan trap, albeit in reverse.

![]() |

This redoutable accoutrement has two horns; the only plausible Asian rhino has only one.

They were looking at pictures of either of the two African species...

(I had a lot of trouble tracking down a still of this one - I'm still not totally sure this is it.

If you know I'm wrong, please let me know. However I have read elsewhere that the

movie war rhinos do have two horns so the story stands.) |

At a different level entirely, even the saccharine and very English Mary Poppins is culpable. The well-known earworm Spoonful of Sugar refers to a robin 'feathering his nest'. Given that it's set in and around London, one might reasonably expect a familiar European Robin Erithacus rubecula. One would in that case be disappointed and surprised.

![]() |

Did they think no-one would notice it was an entirely unrelated and dissimilar American Robin Turdus migratorius?

(Or that it is apparently stuffed, but to be fair the film was made 50 years ago - this year in fact.) |

![]() |

And while we're on Mary Poppins, it seems the use of male gender in the line from the song above

wasn't used lightly. I'm no expert on North American birds, but I'm almost certain this pair comprises two males.

A very bold statement from Disney back in 1964! |

Mary Poppins isn't the only classic under my scrutiny today either. Harry Potter's faithful female Snowy Owl Hedwig regularly went out for nocturnal excursions; unfortunately Snowies are almost wholly diurnal. Also it is unlikely that Harry's evil relatives would have been so disturbed by her hooting (she literally couldn't give a hoot), though they may have got a bit fed up with her

squeaky screeches which didn't rate a mention.

And even the wonderful Finding Nemo got one important point bizarrely wrong. Why would you impose an American Pelican - Brown or Peruvian, I can't be certain, though it's a bit of mix really - onto the Australian east coast?? There are plenty of Australian Pelicans there who would have been happy to step in!

![]() |

| Nigel was never going to pass muster as an Australian Pelican, which is essentially black and white! |

Even a couple of my favourite recreational authors have let me down on occasions. Peter Corris, in one of his historical ventures (I think it was Wimmera Gold) talked about 'the mulga' in western Victoria. Acacia aneura covers a large part of inland Australia - but the only mainland state where it isn't found is Victoria. And Paul Doherty, in his generally well-researched ancient Egyptian series, more than once dressed important people in jaguar skins; I'm pretty sure the Egyptians didn't ever make it to South America!

Does any of it matter? Well if it doesn't bother you, then of course it's not important to you. On the other hand if you saw a car model, or a clothing style, that you knew wasn't possible in that context, it may jar enough to make you question other things that you would otherwise trust, and generally spoil your enjoyment. That's how it is for me with regard to tigers in Africa or Carpet Pythons in the western deserts. And these days in particular, there's really no excuse, is there?

Any contributions anyone?

BACK ON THURSDAY

+San+Pedro+Lodge+area+Manu+1208.jpg)