It's been pretty bitter round our part of the world of late; at 600 metres above sea level, and at the foot of often snowy mountains, we expect cold winters but somehow this one seems harsher than usual. Or maybe, or course, I'm just getting older... Whichever it is, it got me thinking about what it must be like for those organisms who live up in the nearby mountains, another 1300 or so metres higher than here. (And I'm talking about those organisms who can't retreat to an open fire and mulled wine after a day on the slopes.)

| Square Rock Track, Namadgi National Park above Canberra. |

There are, it seems to me, two separate major challenges for organisms who live up in those mountains. You must survive the long harsh winter, and then you must be able to grow quickly and reproduce rapidly in the short time available over summer. Today I've been mulling over the first of these imperatives, and have decided I can identify five basic strategies in use up there.

Stiff Upper Lip (or Macho) Strategy; "pretend nothing's happening and just carry on"

An obvious candidate for this one is the Common Wombat Vombatus ursinus. These large solitary burrowing marsupials stay up in their territory all year round. Of course living in a burrow is a big help, but they must still move out and graze on the tough snow grasses and buried tubers virtually every day, ploughing through the snow and digging into it when required.

|

| Common Wombat near Canberra in milder weather. A big male can weigh close to 30kg. |

|

| Wombat tracks in the snow, Namadgi National Park. |

Smaller vertebrates, surprisingly, can adopt this strategy too however. White-throated Treecreepers and even tiny Brown Thornbills will overwinter, utilising bark crevices which shelter the invertebrates they rely on.

| White-throated Treecreeper Cormobates leucophaea on Snow Gum, Kosciuszko National Park. |

But even more surprisingly a few invertebrates can be Stiff Upper Lippers too. The Spotted Alpine Grasshopper Monistria concinna quite unexpectedly can manage a slow crawl at 0 degrees, but makes no attempt to dig in as its relations do. It turns out that it can survive 'normal' winter conditions in the mountains quite well and has been known (presumably in artificial situations) to survive at -4 degrees for 20 days. It does so by synthesising sorbitol in its blood - in a car we'd call this chemical anti-freeze.

| Spotted Mountain Grasshopper, Namadgi National Park - this one enjoying summer. |

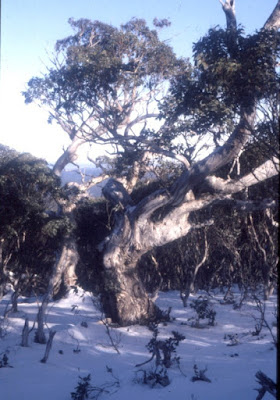

And perhaps the most obvious exponent of this strategy is the mighty Snow Gum Eucalyptus pauciflora, which dominates the high country up to the snow line.

|

| Snow Gum, Mount Ginini, Namadgi National Park. This magnificent old character has probably seen 200-300 winters. |

Snow Gums, unlike northern hemisphere conifers which live with annual snow loads, are not shaped to shed snow, but allow it to pile up on stiff branches and large leaves. Perhaps they have had less time to evolve specialist adaptation, or perhaps our winters, compared with the far north, are not so harsh that other factors are more significant in shaping the trees.

Stay By the Fire Strategy: "grab a good book and wait until it's all over"

Perhaps counter-intuitively, down at ground level winter isn't really the harshest time of year up in the snow country - that comes in autumn, just before the snows, when the ground is exposed and cold and wet are deadly. Once there is a snow cover it provides an insulating layer, which is even more effective when piled over rocks which provide heat sinks. Below the snow the temperature remains even, and when it is at least 50cm deep it never drops below 0 degrees. At this temperature some small mammals can remain active all year round and maintain a healthy weight. One such is the attractive Broad-toothed Rat Mastacomys fuscus, which maintains runways under the snow right through winter in the sub-alpine bogs.

|

| Broad-toothed Rat. Photo courtesy Ken Green, NSW Environment and Heritage. |

| Mountain Plum Pine Podocarpus lawrencei growing over granites, Kosciuszko National Park. In such a situation the under-snow space is even more extensive and significant. |

Woody plants, and many grasses and sedges likewise survive winter under the snow.

| Sedges emerging through the snow, Namadgi National Park. |

Which brings us to the...

Sleep In Strategy; "set your alarm for spring"

As a result of the relatively balmy under-snow conditions just discussed, very few mammals here actually hibernate. One exception is the only marsupial alpine specialist, the Mountain Pygmy-Possum Burramys parvus which inhabits a tiny area of mountain country above the tree line.

|

| Mountain Pygmy-Possum, courtesy Zoos Victoria. |

Echidnas have relatively recently been shown to undergo a partial hibernation in Kosciuszko National Park, going into torpor under the snow for up to six weeks before waking up, going for a wander, then settling down again. I always find it satisfying when nature refuses to stay in the boxes we fashion for it.

The relatively few reptiles which live up in the snow country can only survive winter in a near-frozen state in burrows under rocks and logs; this probably applies to invertebrates such as spiders too.

| Southern Water Skink Eulampris heatwolei, Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve. Survives winter near-frozen. |

The Batemans Bay or Grey Nomad Strategy; "clear off down to the coast or up north for winter"

Batemans Bay is a town on the coast not far from Canberra to where large numbers of human Canberrans migrate at all possible opportunities. Huge numbers of bird species, including many honeyeaters, spend summer breeding in the mountains and head north for winter. The short summers bring a bonanza of food in a concentrated burst, attractive to many species who have no interest in spending winter there.

Some other birds, including Laughing Kookaburras, Red Wattlebirds, Olive Whistlers and White-browed Scrub-wrens, seem to follow the snow line up and down as conditions vary.

Millions of Bogong Moths Agrotis infusa also fly down out of the mountains at the end of summer, which they have spent in cool granite crevices high on the peaks. In their case though this is a reverse migration to that of the honeyeaters; they are heading north to breed on the black soil plains of northern New South Wales and Queensland, where it is too hot to spend summer and where they will all die after laying their eggs. Remarkably no moth makes the trip twice - the precise directions to the granite stacks is hard-wired into the DNA of the eggs in the ground.

|

| Bogong Moth, Canberra. This one is resting on a door mat; they travel at night and many shelter in Canberra homes during a day before moving on again. |

Finally, there is the...

Ultimate Cop-out Strategy; "give up and leave the kids to carry on next year"

Many plants such as daisies die back as the snows approach, leaving seeds in the soil for next spring. Some animals, including many insects, do much the same; blowflies for instance lay their eggs into the soil where their larvae survive winter near-frozen.

Anyway, I hope my anthropomorphic approach to teasing out a pattern in these strategies hasn't put you off too much. I find a bit of fun can help the understanding process. With luck that's how you see it too... Stay warm until next time!

BACK ON TUESDAY, TO ACKNOWLEDGE BELGIUM'S NATIONAL DAY